First Edition

“Streaming Devalues Music”

Interview with Julia Holter

Photo Credit © Chris Votek

This interview has been edited for publication.

Don Franzen:

I’m delighted to be speaking with Julia Holter, a phenomenal independent musician, composer, songwriter, all-around musical talent, original in many, many ways. But more recently you were in the headlines for picketing Spotify in Downtown Los Angeles as part of a protest over the paltry royalties that end up in the pockets of working musicians (see https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2021-04-19/spotify-artists-royalty-rate-apple-music).

Thank you very much, Julia, for taking the time to talk to me.

Julia Holter:

Thank you for having me. Glad to be here.

Don Franzen:

Your career started about a decade ago with some wonderful breakthrough albums that rightfully got a lot of attention, in particular your album Tragedy, followed by Ekstasis, which then led to some ecstatic reviews, in particular in Pitchfork. Then you got your first label deal and started to release albums commercially. What was the environment in the recording business like a decade ago when you first entered it?

Julia Holter:

I think some things have changed, particularly with streaming, which we will discuss, but it doesn’t feel totally different overall to me. Maybe I’m still trying to understand what the differences are. I actually think we’re at a point now after COVID where things might have changed a lot for the music industry, and so that might be the turning point. But streaming for sure has changed things in ways I’m still learning about. I think it was [previously] much more about downloading, and I don’t even know at what point Spotify started gaining traction, because I was kind of not paying attention, since I’ve never used it. I still use iTunes! But definitely it was a lot more about downloading. Mp3s and CDs and vinyl were a thing too, of course, and even cassettes, actually. I think my first release was a cassette. But cassettes and vinyl are obviously still around in a significant way, especially vinyl. And with things like Bandcamp, and in the relatively small independent music worlds I’m around, there is still a little ecosystem of downloading and supporting experimental music. But I’ve noticed streaming changing things for artists in recent years in a couple ways—economically of course, but also, this kind of playlist mentality I find really destructive for creative music. It’s an obsession with constant content and trying to fit into something that will be favored by a corporate algorithm, etc.

Don Franzen:

You also have a performance career, but as a recording artist. What’s been your experience with streaming as far as the ultimate payout to you?

Julia Holter:

To be totally honest, I haven’t paid a lot of attention until recently. The past year I’ve started learning about streaming. Basically, my experience is that it’s relatively negligible [income], and my thoughts had been “If it’s negligible for me, what must it be for other artists who started out more recently?” It’s probably getting worse the more recently you started out. So I started learning about it. I’ve calculated that for one year, I received, for example, a little more than $4,000 for 5.5 million streams on Spotify. That’s for the master recording side… it’s something like $0.0076 per stream, because I am signed to a label, and this is the situation for a lot of artists of course. Actually, Spotify pays less than most of the platforms, but it’s complicated to talk about how it pays, because it’s not a straightforward answer, but $0.0038 per stream is the approximate rate. They don’t pay per stream, but that’s the approximation. That is assuming that the artist is not signed to a label, and if you’re signed to a label, then you get even less, as I mentioned with my streams.

Don Franzen:

Just to explain, that’s because they pay that money to the label, and then the label pays the artist according to whatever the agreement is with the artist.

Julia Holter:

Right. Spotify makes deals directly with labels. They pay the labels directly, and then the label pays the artist, and this is true for most labels. I have a good relationship with my label, and I like my label a lot, but this is how it works with Spotify.

Don Franzen:

The agreements between the labels and Spotify are private agreements. They’re not public. They’re not registered anywhere. So, it’s whatever deal they make.

Julia Holter:

Yes. I don’t even know if it’s public knowledge what these agreements are. I think it actually is secret. I think that all the agreements they make with each label are private, so I couldn’t even tell you.

Don Franzen:

Similarly, the deals between the labels and the artists are private agreements. So it depends on the artist’s agreement. Some artists may have better agreements than others, but the bottom line is that it’s sort of a trickle back to the artist, right?

Julia Holter:

Yes. Even if you don’t have a label, it’s $0.0038 per stream. Not great, you know?

Don Franzen:

That’s best-case scenario. That’s where you’ve got the deal directly with Spotify and no label in between you and Spotify.

Julia Holter:

Right.

Don Franzen:

As you got to know more about this, you decided you wanted to take some action. What led up to your showing up in downtown LA in front of Spotify?

Julia Holter:

The way that I feel about it is that Im actually doing okay. I’ve had a very lucky experience in music, and I have revenue coming out of publishing — for which streaming does not pay very well, actually — but I’ve written on various projects that aren’t just my own recordings. I’ve done enough at this point that I do have relatively reliable royalties that I feel lucky for; for someone who makes music they want to make, that feels really lucky. So I’m doing okay, and I’ve been able to tour – or, we will see in the future, when it’s not COVID times, what will happen. I’ve been really lucky, and I’ve had a good relationship with my label and with the various labels I’ve worked with.

But I’m very worried about creative musicians, and I’m worried about the future of music, and that’s why I was interested in being a part of the Union of Musicians & Allied Workers. I was invited by Damon Krukowski, a friend of mine, to curate part of a charity compilation for it, and so that’s how I learned about UMAW. I just was reading about bringing together musicians who normally haven’t unionized because they’re not salaried workers or they’re freelance. So, it’s been hard for them to be part of a musician’s union. I hadn’t paid much attention to my streaming royalties because they were pretty insubstantial and extremely confusing to me… So, I just wanted to learn more about it, and I knew that other musicians were, especially musicians just starting out, really struggling.

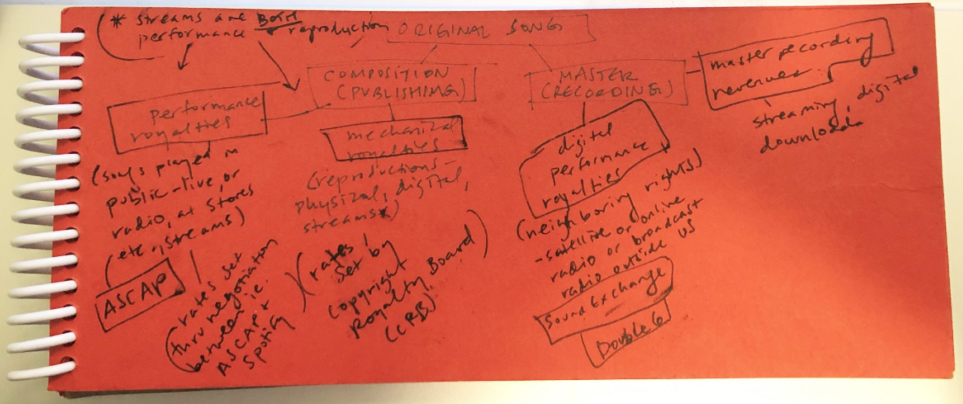

I also find the playlist culture I mentioned before really offensive, having to put out as much content as possible and constantly thinking about “Oh, your track has to be short so that people can enjoy it on Spotify,” or “The first track of your record has to be really a kicker, “because that’s the way people listen on Spotify.” Meanwhile, this platform is not paying musicians properly. It all seemed like it needed to be explored, and I was intrigued that there were musicians getting together to discuss it, and again, I just didn’t know much about it. So, I’ve learned more about it this past year, and it’s still funny how illiterate I am about it, but I’m learning. Royalties are so complicated. I have a chart I’ve written out to help me, and I have to refer to it all the time because it’s so confusing.

Photo Credit © Julia Holter

Don Franzen:

Tell us a little bit about the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers and your involvement in it.

Julia Holter:

When I first heard about the UMAW, I started going to streaming meetings. There are many other parts of UMAW too. Streaming is just one committee. There are a lot of great subcommittees that I would like to be involved in when I am able to find more time. There haven’t been a lot of forums in which musicians can discuss a lot of these things. Especially early on, when I wanted to start working with musicians, I did not know what the standards were for how labels should be treating musicians, or how much you’re supposed to pay another musician things like that. There are limited standardized discussions about these things in the freelance music world. I think organizing these discussions like UMAW is doing will help the music world a lot.

Don Franzen:

Was it the UMAW’s idea to picket Spotify?

Julia Holter:

Yes, and I would describe the event specifically as an in-person action to deliver the UMAW Justice at Spotify demands to Spotify. There was a feeling, once that was presented publicly online, that we needed to do something in person, which was also of course very challenging because of COVID, to really put pressure on Spotify to know that we’re not just forgetting. That’s the hope, because they function very much the way that tech companies function, where it’s all about hoping no one cares that you’re making the most money with investments, not actually making a profit, and not actually paying people right. It’s a tech company model that is really problematic, pretty similar in some ways to what you see with Uber. So it seemed important to people in UMAW to continue to make their demands so Spotify didn’t think everyone had forgotten about it. The Justice at Spotify campaign started in 2020. It was a year ago that I started talking with them, and we started having meetings in the streaming committee and put together a list of demands of Spotify. First, it’s “pay us at least one cent per stream.” Secondly, it’s “adopt a user-centric payment model.” In addition, it is a demand to make all closed-door contracts public, and reveal existing payola, then end it altogether. It also demands Spotify credit all labor in recording, and end legal battles intended to further impoverish artists. On the website, more information can be found about it.

Don Franzen:

What was it like down there in front of the Spotify building? Weren’t you finally asked to depart, and did someone come along and ask you to leave?

Julia Holter:

When it first started, talking with UMAW people they [were] mostly on the East Coast. So, I didn’t really know a lot of the people in LA, and there weren’t a lot of the people in the committee in LA. So, I was coordinating it with another UMAW member, who has been involved in setting up an LA local group. He officially led it, and I was connecting him with the central discussion in the streaming committee. I’ve never organized something like this. I can’t say I am great at that—I know some people truly are—but I was working with him and with UMAW to try to make it happen, and they were a good group of people, all different musicians, and a lot of people I didn’t know showed up (in fact, mostly people I didn’t know). Because it was COVID, it was particularly strange, but it was really cool to see people coming out and being really friendly and wanting to work together.

Don Franzen:

Any reaction from Spotify as a result of the protest?

Julia Holter:

Yes, well, whether or not it was related to just what UMAW did, or just in general a response to the global outcry we’ve been seeing from artists all over the world, they issued this “Loud and Clear” statement. Spotify issued a statement and actually built a website called “Loud and Clear,” claiming that they hear musicians’ questions and attempt to be clear, but it wasn’t really answering any of the questions or meeting any of the demands.

Don Franzen:

Please go over what your demands were.

Julia Holter:

So, before I go into the specific demands, to me, the biggest issue, and I feel like this is in line with a lot of tech companies in general and how they function, [is] devaluing things. Spotify is actively devaluing music, and I think it’s a big concern for creativity as much as it is for the economy of being an artist. They go hand in hand, obviously, but it’s just a total devastation of the value of music for a lot of different reasons. So, the demand is at least one cent per stream. Like I said, the current average rate per stream is $0.0038 per stream. Artists are simply asking to be paid one cent per song stream or the equivalent in local currency.

Don Franzen:

There are other platforms that do pay close to that amount or that amount, right? A penny per stream.

Julia Holter:

That’s correct. Exactly-

Don Franzen:

Like Apple Music, for example.

Julia Holter:

Apple pays around close to one cent per stream, and this is one of the ways Spotify is devaluing music, that it pays so little per stream. Spotify is the only platform, I’m pretty sure, that has a free tier, and so this is a big part of the devaluing. This free tier is used a lot in [Spotify’s] arguments “Oh, [we’re] making music accessible to everyone,” but it’s totally ripping off artists. If you look at most artists’ [royalty statements] and most people I talk to who have statements, it’s all Spotify. The streaming is dominated by Spotify. Any other, including Apple Music, the royalties are very small compared to Spotify. The percentage of streaming royalties are mostly Spotify. Doesn’t mean there’s a lot of [other services], but it just means that of all the streaming services, it’s going to be mostly Spotify. They really dominate, and one of the ways they do it is by being the cheapest for listeners.

Don Franzen:

Well, that’s one demand, a penny per stream. What are some other demands?

Julia Holter:

The user-centric payment model. This is probably something a lot of [people] don’t know about, but Spotify currently pays artists with a pro-rata model, which is very confusing, but it’s basically like all the revenue is pooled together and then distributed to artists based on a percentage of all total streams. It basically means that artists at the very top get the greater percentage of streams, and all other artists receive much less, and so in a user-centric model, artists would be paid directly according to the number of streams they receive. We’re not paid per stream.

Don Franzen:

That’s a very interesting point, and it sounds like one that should be acted upon in fairness. What other issues is the UMAW bringing up?

Julia Holter:

Make all closed-door contracts public. There’s a lot of lack of transparency. As we talked about earlier, they make closed-door contracts with labels, and distributors for payments, and so we’re demanding that they’re not secret.

Don Franzen:

Are there further issues?

Julia Holter:

Yes. Reveal existing payola, then end it altogether. There’s question about whether the word “payola” can be applied, and that’s a separate discussion, but UMAW believes it is payola. For example, there’s a mode in Spotify called the Discovery Mode, where they’re offering artists a lower royalty rate, but the artist will get preference in the algorithm in exchange for lower payment rates. This is like a pay-to-play practice, kind of like illegal payola in terrestrial radio.

Don Franzen:

Like getting in front of the line, right? We pay you less, and we bump you up in our algorithm?

Julia Holter:

Yes; this is another way that they devalue music. If you think about how the system is pro-rata, not user centric, you realize that when they do this, then they’re prioritizing certain artists, [and] the artists not getting that priority in the algorithm are getting [fewer] plays. It affects them in that whole percentage algorithm too. When you have something like this Discovery Mode, where there are certain artists getting elevated in the algorithm, all other artists suffer. If it was all just user centric, it wouldn’t affect everyone else as much. Since it’s all a percentage, when you have this shift in the algorithm, it’s not only those other artists aren’t getting that boost in the algorithm and as many plays, but also those artists who are getting the plays are taking up more of that percentage — so in addition to just getting more plays, they’re taking away plays from other artists.

Don Franzen:

Right. So it magnifies the percentage that certain artists are getting at the expense of other artists.

Julia Holter:

Yes, that’s what I’m trying to say. There are a couple more [demands]. There’s the demand to credit all labor in recordings, which I kind of was pushing for us to add. I think that the musicians I work with are all so great, and I think that the way that Spotify presents music — and this is true of all streaming services as well — you just don’t have the crediting. It’s not well done on their platform. That’s an important thing.

Don Franzen:

It’s hard to know who all the musicians were or who the producer was or who the mixing engineer was, all the information that people in the music business like to know. It’s hard to find.

Julia Holter:

Exactly, and like I said, that started with digital stuff. It wasn’t just Spotify, but that’s something that needs to be worked on, and everything they’re doing with devaluing music really affects artists who aren’t the main performer or main composer on a recording. The final demand is to end legal battles intended to further impoverish artists. Spotify has been suing the Copyright Royalty Board to reduce the mechanical royalty rate they set.

Don Franzen:

So, these are all important points, equitable points, that need to be considered. What do you see as the future? Do you think there’s a future in which there will be greater equity in the distribution of streaming revenue?

Julia Holter:

I like to think so. So, basically, yes. I think there’s a lot of room for improvement. Considering that Spotify tripled in valuation in 2020 during COVID, with at least $10 billion added last year, I think, it reached a total valuation of over $60 billion. I’m not sure of its current value, but that’s basically how it is, and considering that the three major labels are jointly making over $1 million an hour from streaming, I think there’s a lot of room for improvement. The problem is there are a lot of assumptions that there isn’t money in music because it’s digital and free. This is the argument Spotify’s often made, that they’re saving musicians from not making any money, and this is false, because there’s actually tons of money in streaming, and it’s just not going to musicians.

Don Franzen:

There’s movement going on in other countries as well?

Julia Holter:

There’s a lot of movement happening. For example, there’s the Broken Record campaign in the UK, that’s gotten the House of Commons to address the issue, and they’re really making headway on that, and they’re really making people aware. UMAW’s been very involved in making people aware and inviting musicians to take part in that whole process. There’s a lot happening with it right now. There was just a UN report that we’ve been studying in UMAW. The World Intellectual Property Organization, which is part of the UN, did a study on the artists in the digital music marketplace and specifically with streaming, and it’s really just all about how unfair it is for artists [See the report here: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/copyright/en/sccr_41/sccr_41_3.pdf]. One of the things that someone like Tom Gray, who’s part of the Broken Record movement, is putting forward is that there is room for these things to improve. In the UK, there’s an interest in this equitable remuneration, which is basically related to digital performance royalties, also called neighboring rights, and there’s room in there to really improve the more equitable royalties for musicians including artists who are not the main artist on the recording. Right now, [in the US] you don’t have neighboring rights in the way you have them in the UK and Europe. Well, [there are] digital performance royalties for broadcast radio, but only outside of the US. [In the US] it’s facilitated through SoundExchange, but [only for non-interactive digital radio.] These would be royalties that would go toward not just me, Julia Holter, but also the performers on my recordings, and these would be royalties that on the master recording side [would be] for all artists. In the current situation, streaming does not count in this category (the argument being that streaming is not always active, even though it’s considered “interactive”). It’s passive often, a form of “non-interactive” listening. It’s a hybrid of the two. They have settings where they’re playing your stuff passively the way radio does, and so the argument could be that they would be included in this. This is really specific, but that’s one avenue that I think is promising. I hope it is discussed more in the US. There are all kinds of ideas. In the case of UMAW, the current focus is Spotify because it’s really dominating, and in doing so, Spotify is devaluing music, dominating in this kind of way that’s not fair.

Don Franzen:

I think the theme that’s come through in everything you’ve been saying is that music is getting devalued in lots of different ways. Spotify is one example, but you’ve just mentioned a number of others, including the absence of neighboring rights in the United States, for the most part. So it looks like, going forward, there’s a lot to do to create equity for working musicians in the recording industry.

Julia Holter:

That’s right.

Julia Holter is a composer, performer, and recording artist based in Los Angeles. Her interest in sonic mysteries has led her to record in various settings—in her home, outside with a field recorder, and in recording studios—as well as to perform live, often with a focus on the voice and the space between language and babble. Holter’s music is multi-layered and texturally rich. She has amassed a body of work that explores melody within free song structures, atmosphere, and the impulses of the voice. She has released five studio albums: Aviary (2018), Have You In My Wilderness (2015), Loud City Song (2013), Ekstasis (2012), and Tragedy (2011). Holter has performed her music at venues and festivals throughout the world with an ensemble of creative musicians. She has written music for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and other ensembles, as well as scores for the films In My Own Time: A Portrait of Karen Dalton (2020), Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020) and Bleed for This (2016) and the TV show Pure (2019).

© 2021 Your Inside Track LLC

Your Inside Track reports on developments in the field of music and copyright, but it does not provide legal advise or opinions. Every case depends on its particular facts and circumstances. Readers should always consult legal counsel and forensic experts as to any issue or matter of concern to them and not rely on the contents of this newsletter.