Third Edition

New and Noteworthy:

Recent Developments in Music and Copyright

By Don Franzen

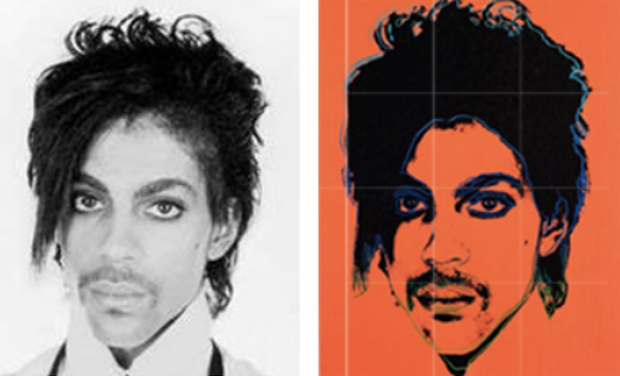

WARHOL GOES TO THE SUPREME COURT

In a case that could have far-reaching impact on all the creative arts, including music, the Supreme Court has agreed to take up the controversial decision of the Second Circuit in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith. The case originated when the Andy Warhol Foundation sued photographer Lynn Goldsmith for a declaration that Warhol’s series of lithographs entitled the “Prince Series” did not infringe her iconic photograph of Prince taken in 1981. The District Court ruled in Warhol’s favor, finding that the Warhol prints constituted “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photograph, but the Second Circuit reversed, finding that “fair use” did not apply. Comparing the two visual works, the Second Circuit concluded “the Prince Series retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements” so that the “Prince Series is not ‘transformative’ …”.

On March 28th this year, the Supreme Court granted the Warhol Foundation’s Petition for Certiorari, and on June 10th, the Foundation filed its brief [See here] arguing the Second Circuit’s application of the “transformative” element of the fair use doctrine is “cramped” because it focuses on whether the new work retains the “essential elements” of the prior work, rather than on whether the new work conveys a new “message or meaning.” Warhol also argues the Ninth Circuit has it right, by emphasizing new “message or meaning” as the touchstone of transformative analysis, citing Seltzer v. Green Day, 725 F.3d 1170, 1175 (9th Cir. 1994). The case represents a rare opportunity for the Supreme Court to provide guidance on the meaning of the somewhat murky “transformative” test in fair use doctrine. As the Ninth Circuit commented in Seltzer, “… there is no shortage of language from …. court elucidating (or obfuscating) the meaning of transformation.”

DID YOU GET A RELEASE FOR THAT ALBUM COVER?

Spencer Elden, who was photographed as a baby and his image used on the iconic cover of Nirvana’s Nevermind album, filed suit in the Central District of California in August 2021, alleging the photo “exposed Spencer’s intimate body part and lasciviously displayed Spencer’s genitals from the time he was an infant to the present day.” Baby Elden is depicted underwater grasping for a dollar bill dangled in front of him. According to the suit, this was tantamount to depicting the baby as a “sex worker.” Also alleged in the complaint, no parent or guardian release was signed, and verbal promises to cover the infant’s genitals were not honored. Elden’s case did not get off to a good start; a motion to dismiss was granted by Judge Fernando M. Olguin Moral in January this year, but Elden was granted the opportunity to file an amended complaint. Click here to read the article on NPR. Moral of the story: Get a written release for any album photoshoot! Note that California law specifically allows for a parent or guardian to give a release for use of a photograph, California Code, Civil Code § 3344(a).

DUA LIPA: BAD NEWS COMES IN THREES

For Dua Lipa, bad news in the form of lawsuits comes in threes. Twice in March of this year, the pop icon was sued for copyright infringement stemming from her hit song Levitating. The first lawsuit was filed in the Central District of California on March 1st by members of the band Artikal Sound System, who are the authors and copyright owners of the 2017 reggae composition Live Your Life. Without elaboration or analysis, the complaint alleges, “Levitating is substantially similar to Live Your Life. Given the degree of similarity, it is highly unlikely that Levitating was created independently from Live Your Life.” The complaint can be read here. The second lawsuit was filed on March 4th in New York on behalf of L. Russell Brown and Sandy Linzer, the composers of Cory Daye’s 1979 disco song Wiggle and Giggle All Night and the 1980 song Don Diablo. Unlike the California case, this case sets forth musical examples in the complaint, including bar-by-bar comparisons between Levitating, Wiggle and Giggle, and Don Diablo. The complaint can be read here. The two lawsuits offer contrasts in pleading style: the complaint in the Live Your Life case asserts “substantial similarity” without detailed musical analysis, whereas the Wiggle and Giggle complaint offers several specific musical examples. By its lack of specificity, the California suit may be immune from a motion to dismiss (although discovery will require the plaintiffs ultimately to lay out their grounds for claiming substantial similarity), whereas the New York case might, by being more detailed, expose itself to an early motion to dismiss.

The third shoe dropped for Lipa in June of this year, when photographer Robert Barbera sued her in the Central District of California for using several photographs of Lipa herself on her Instagram account. As alleged by Barbera, he has registered copyrights in the photographs, and Lipa “without permission or authorization … actively copied, stored, and/or displayed Plaintiff’s photographs on [her Instagram account] …” The images have since been taken down, according to the complaint, which can be read here. Warming to artists: don’t assume just because the image is of yourself you have an unfettered right to use it!

CAN AI BE AN AUTHOR?

The debate on AI and copyright continues. As reported in Issue No. 2 of this Newsletter, The Review Board of the US Copyright Office recently ruled a two-dimensional artwork entitled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” could not be registered for copyright protection because it was authored by artificial intelligence without any creative input or intervention by a human being. Now Dr. Stephen Thaler (self-described as “in the business of developing and applying advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems capable of generating creative output,” and who unsuccessfully applied for a copyright in the name of his “Creativity Machine”) has filed suit in Federal Court to overturn the Review Board’s decision. In Thaler v. Perlmutter, filed June 2, 2022, [See Complaint here]. Dr. Thaler alleges that the Copyright Act gives “protection to ‘original works of authorship,’ a phrase which Congress left purposely undefined and for interpretation by the courts,” and “at no point does the act limit authorship to natural persons.” He also alleges “Copyright protection for AI-Generated Works is entirely consistent with the text and purpose of the Act.” Thaler’s complaint makes for interesting reading, and makes two arguments to support his position: one, that while the “Creativity Machine” is the “author” of the artwork, Thaler is the owner of the artwork under the personal property doctrine of “accession” (property created by a person’s property belongs to the owner); and second, analogous to the “work for hire” doctrine, that the relationship between Thaler and the Creativity Machine is functionally equivalent to an “employer-employee” relationship. The latter argument would seem to run afoul of Thaler’s principal motive in bringing this case, his desire to have the Creativity Machine declared an “author,” since in a work for hire situation the employer is deemed the author. 17 U.S.C. 101.; (See https://www.copyright.gov › circs › circ09.pdf ) “If a work is made for hire, an employer is considered the author even if an employee actually created the work” (italics added). With this case the issue is joined, and the courts will have to decide if AI can be an “author” (absent legislative action to clarify this question).

Meantime, Dr. Thaler’s efforts to have the Creativity Machine be recognized for authoring IP met with another disappointment. In a patent case, on August 5 this year, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that an “inventor” must be “a human being,” upholding a District Court decision that reached the same conclusion. The appellate decision can be read here. Is the Supreme Court ready to take these cases?

CAN YOUR LYRICS SEND YOU TO PRISON?

In a case that touches upon serious First Amendment issues, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals has been asked to decide whether the use of lyrics written by a rap artist can be admitted to prove guilt in a criminal trial. In the case against 17-year-old Tommy Canady for the murder of one Semar McClain, age 19, the evidence against Canady was largely circumstantial: no witness or evidence actually placed him at the crime scene. But, along with evidence that the two were seen arguing before McClain’s death and that Canady possessed weapons akin to the ones the prosecution claimed were used to murder McClain, prosecutors were also allowed to play to the jury excerpts from Canady’s rap song “I’m Out There” containing lyrics arguably depicting a murder similar to the one at trial. The jury asked to hear the song twice; it is hard to escape the conclusion that the song’s lyrics failed to affect the jury’s decision to convict. The court sentenced Canady to a minimum of 50 years in prison. Reliance on lyrics to support criminal prosecutions seems to occur largely in cases involving rap artists. Would there be more reluctance to use lyrics to convict a country-western songwriter? While using rap lyrics as evidence may be problematic where First Amendment issues are involved, another recent case illustrates when the lyrics may be probative of a crime. Recently, LA rapper Nuke Bizzle pleaded guilty to unemployment insurance fraud after rapping about “go[ing] to the bank” with a stack of unemployment checks. Click here to read the article. Some form of balancing test weighing free speech concerns, prejudice and probative value is needed. Federal and state legislation has been proposed to provide guidance to courts on the admissibility of lyrics in criminal cases. See Federal here and California here. A recent op-ed piece in the New York Times argues for more stringent standards before such evidence can be introduced at trial. Click here to read the New York Times article. The background for the New York Times article may be found here.

PANDORA STRIKES BACK!

As reported in Issue No. 2 of this newsletter, Robin Williams’ estate recently brought a copyright infringement lawsuit seeking millions of dollars in royalties from Pandora in what may prove to be a precedent-setting case for payment of royalties to stand-up comics. Other prominent comics filed similar claims, and the cases have been consolidated as In re PANDORA MEDIA, LLC COPYRIGHT LITIGATION Master File No. 2:22-cv-00809-MCS-MAR (Central District California). The basic theory of the comics’ case is that Pandora has failed to pay royalties on the copyright owned by each of the comedians in their routines (as opposed to license fees for streaming videos of their acts). Pandora was not amused. In a counterclaim filed on May 5th this year, the streaming platform has struck back with a novel theory: that the combined actions brought by the comedians amount to a “cartel” seeking to set prices, amount to ty-in sales, and an attempt to monopolize the “U.S. market for the rights to comedy routines embodied in comedy recordings” in violation of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. [See Pandora’s counterclaim here]. Lead counsel for the comics, Richard Busch, reacted to Pandora’s counterclaim with the following quote to Billboard: “We have seen it, we vehemently disagree with it legally and factually, and we will be responding appropriately.” Prediction: Pandora’s counter-offensive will run into trouble under the Noer Pennington Doctrine (here), which generally exempts petitions for redress of rights in court from Antitrust liability.

RECORDING INDUSTRY SCORECARD: LABELS WINNING, ARTISTS GAINING?

By most metrics, 2021 was a bumper year for the recording industry. As reported by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), paid streaming was up 23% to $9.5 billion. The average number of subscribers grew 11% to 75.5 million. Ad-supported streaming revenue grew 47% to $1.8 billion. Digital downloads fell 12% to $587 million and accounted for just 4% of total revenue. Physical sales rose 42.3% to $1.66 billion despite a 21% decline in CD sales. Overall, the industry commanded nearly $15 billion. The catastrophic downturn of the recording business, triggered by widespread file sharing in the first decade of this century, has reversed with steady growth—fueled by streaming—in recent years. Recent economic studies argue copyrights in music are more valuable than ever. Click here to read the study.

What remains to be addressed is a more equitable distribution of these surging revenues between labels and artists. One encouraging trend in this area is the weakening of big labels’ insistence on all-encompassing “360” Deals that divert a percentage of an artist’s overall entertainment earnings to the label. According to a recent Billboard article, leading music lawyers report that “the 360 Deal has become more of a starting point than a foregone conclusion.”

Another development is a recent self-described “historic” deal between music trade associations and collecting societies in France, setting a “minimum” streaming royalty rate of between 10% and 11% for artists—in effect lifting up artists with lower contractual rates. Click here to read more.

And in a positive development for songwriters, the major labels and publishers have reached an agreement before the Copyright Royalty Board to increase songwriter mechanical royalties on physical products and downloads to 12 cents for every track sold (up from the 9.1 cent rate in effect since 2008). Click here to read more.

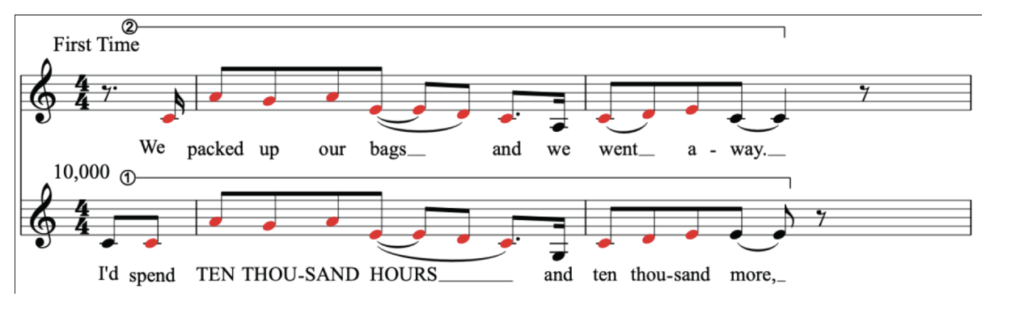

FORTY YEARS AND 10,000 HOURS LATER

A lawsuit filed in the Central District of California in April this year alleges the song 10,000 Hours by Justin Bieber and duo Dan + Shay plagiarizes a song written over forty years ago by Palmer Rakes and Frank Fioravanti. The complaint is brought by a Nevada LLC, Melomega, which claims ownership of the earlier song’s copyright. As alleged in the complaint, “[o]ne need only listen to First Time and the infringing 10,000 Hours to discern the unmistakable similarities between the songs.” In some detail, the complaint presents the similarities in a bar-by-bar comparison, for example, as follows:

According to the plaintiff’s expert, Dr. Alexander Stewart, “First Time … and 10,000 Hours are practically the same song, and given the degree of similarity in these passages and other details … I consider it almost impossible that 10,000 Hours was created independently from First Time ...” Relying on the doctrine of “striking similarity,” Melomega also alleges access to First Time is “inferred,” but goes on to assert access on the basis that the song was released repeatedly via Orchard between 2017 and 2019 and widely available. Background on this case can be found here, and the Complaint can be read here.

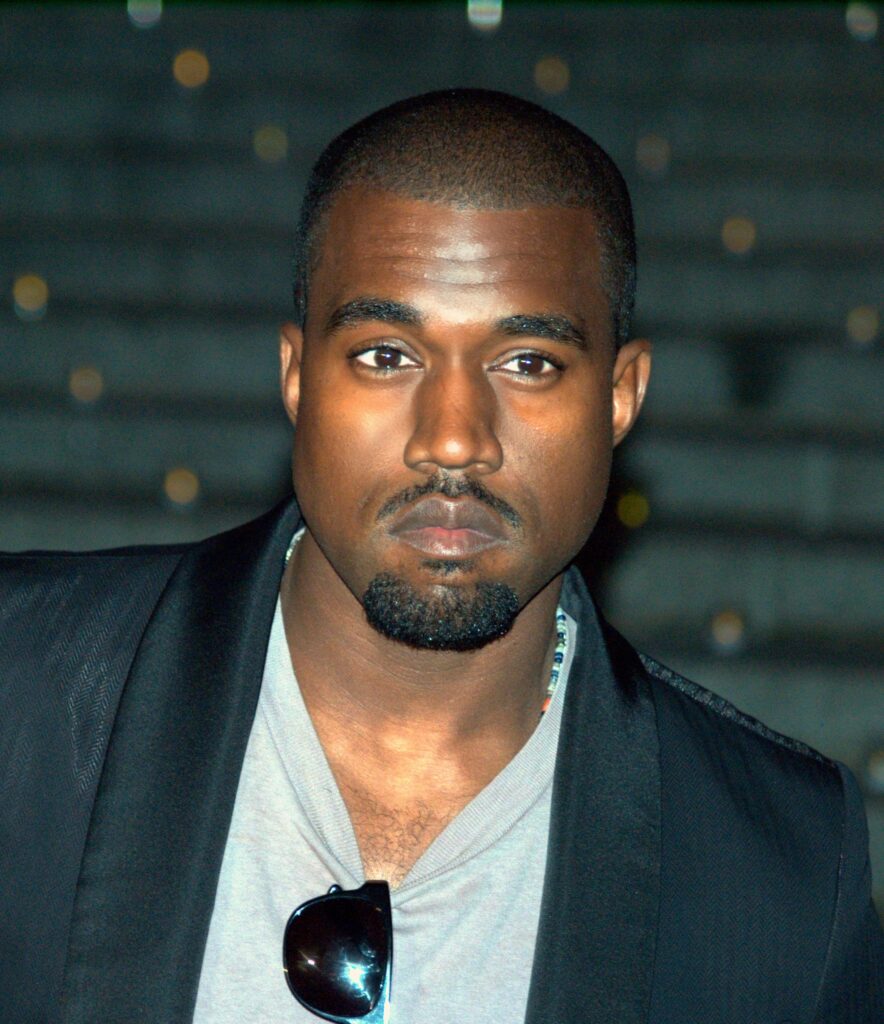

SHALT THOU STEAL FROM A BISHOP?

Ye, the artist formerly known as Kanye West, stands accused of stealing a recording by Texas Bishop David P. Moten in Ye’s 2021 album Donda. In a lawsuit filed in the Northern District of Texas in May of this year, Bishop Moten alleges that over a minute of Ye’s five-minute song Come to Life uses unlicensed samples of a recording of a sermon by Moten, such that “twenty percent (20%) of the entire sound recording Come to Life is comprised of unauthorized, unlicensed samples of the Sermon.” At issue are both the Bishop’s copyright in the sermons themselves as well as his claim to own the copyright in the recordings. The complaint seeks unspecified damages, attorney’s fees, and costs. The complaint can be read here.

IS A RECORD PRODUCER AN AUTHOR?

Can a record producer claim to be a co-author of a song? That’s what a recording company who hired a producer to work on a hit album by 80s pop star Toni Basil argued. But in a memorandum decision (not for publication) in May this year, the Ninth Circuit upheld a trial court decision that the indicia of joint authorship were not present. The producer was not, the court agreed, a “creative mastermind,” and the process of recording and mixing were done at the singer’s “direction consistent with her creative vision.” Citing the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Aalmuhammed v. Lee, 202 F.3d 1227 (9th Cir. 2000), the panel concluded all three factors developed in that case went against the producer: he did not exercise control over the recording, there was no objective manifestation of an intent to share authorship, and the success of the recording did not depend on the contributions of both producer and singer. Whatever may be true based on the facts of this case, a general rule cannot be abstracted from the decision. Some producers are equals to the musicians; Exhibit 1 being the case of George Martin, sometimes known as the “Fifth Beatle.” The court’s decision can be read here.

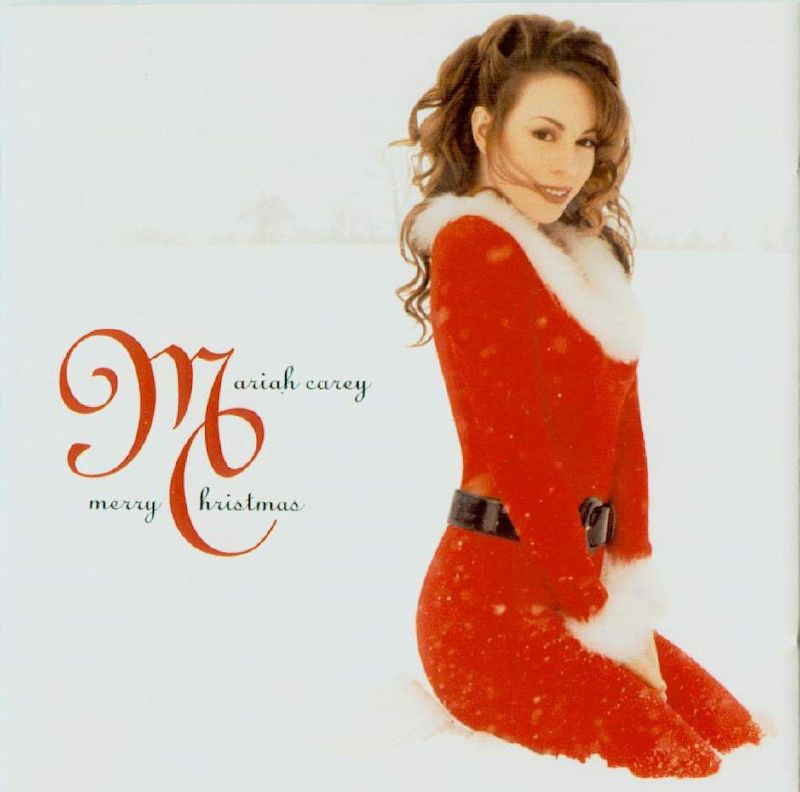

ALL I WANT FOR CHRISTMAS IS NO MORE LAWSUITS

In June, Mariah Carey was sued by Andy Stone, a Mississippi songwriter, for allegedly stealing his song All I want for Christmas is You in her 90s smash hit with the same title. The complaint, filed in the Eastern District of Louisiana, where Stone states that he recently bought a copy of Carey’s album, alleges that Stone wrote a song by the same title years before Carey released her album, and asserts causes of action in copyright, trademark and unjust enrichment. Tellingly, the complaint does not allege similarity between the songs apart from having the same title. A motion to dismiss may be expected, relying on the axiom that copyright protection does not extend to titles alone. See https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-protect.html (“Copyright does not protect names, titles, slogans, or short phrases”). The complaint can be read here. Background on this can be found here, including the interesting observation that “there are 177 copyrighted songs with the title All I want for Christmas is You, including dozens that were written decades before [the plaintiffs’] version.”

A BRIDGERTON TOO FAR?

Songwriters Emily Baer and Abigale Barlow (known as Barlow & Baer) became TikTok sensations when they composed and performed songs based on the Netflix hit tv series Bridgerton (adapted from the romance novel by Julia Quinn). Both still in their 20s, Barlow & Baer went on to release an album, and in 2022 won the Grammy for Best Musical Theater recording. Billed as the Unofficial Brigderton Musical, all this was done without express permission from Netflix, Quinn, or the series producer Shonda Rhimes. But now, with a live stage musical, Barlow & Baer have gone a Bridgerton too far, or so at least alleges Netflix, which on July 29, 2022, filed suit in the District Court of Columbia for copyright and trademark infringement against the young songwriters. As alleged in the complaint, “Netflix owns the exclusive right to create Bridgerton songs, musicals, or any other derivative works based on Bridgerton. Barlow & Baer cannot take that right—made valuable by others’ hard work—for themselves, without permission. Yet that is exactly what they have done.” The complaint alleges a recent live stage production at the Kennedy Center “featured over a dozen songs that copied verbatim dialogue, character traits and expression, and other elements from Bridgerton the series.” The complaint can be read here. When asked for comment by the NY Post, author Quinn replied: “I was flattered and delighted when they began composing Bridgerton songs and sharing with other fans on TikTok. There is a difference, however, between composing on TikTok and recording and performing for commercial gain.” Shonda Rhimes also gave a statement to the NY Post, saying, “What started as a fun celebration by Barlow & Baer on social media has turned into the blatant taking of intellectual property solely for Barlow & Bear’s financial benefit.” The issue of fair use is sure to figure in the outcome of this case, and the pending Supreme Court Warhol case may provide guidance to this case’s outcome.

Don Franzen’s legal practice covers the spectrum of the entertainment industry, including recording, television, film, live entertainment, copyright, trademarks, endorsements, corporate, tax and visa issues, and non-profit organizations. His clients include composers, producers, vocal and instrumental artists, as well as performing arts organizations. In addition to providing business and legal advice, he has acted an as a producer on recording, video, and theatrical projects. He also has established an expertise in commercial civil litigation, including appellate practice (State and Federal). He has lectured on entertainment law for Eastman School of Music, the Santa Monica College Academy of Entertainment, the Colburn School of Music, the California Institute of the Arts, and is a visiting professor at the Berklee School of Music (Valencia, Spain). Since 2009 he has taught courses on music and the law at the Herb Albert School of Music, University of California Los Angeles, and effective 2016 has been appointed as an adjunct professor as part of its Music Industry Program. Since 1997 he has been chosen as a Fellow of the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Southern California. He serves as the Legal Affairs Editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and has authored various essays and book reviews on legal topics. He is a founding director of the Los Angeles Opera, and a director of Heyday Books, and the Denyce Graves Foundation. In addition to his native English, he speaks Spanish, Italian and conversational German. He is married to Dale Franzen and proud father of three children. He may be reached by e-mail at [email protected].

© 2022 Your Inside Track™ LLC

Your Inside Track™ reports on developments in the field of music and copyright, but it does not provide legal advice or opinions. Every case discussed depends on its particular facts and circumstances. Readers should always consult legal counsel and forensic experts as to any issue or matter of concern to them and not rely on the contents of this newsletter.