Fifth Edition

New and Noteworthy:

Recent Developments in Music and Copyright

By Don Franzen

HAS THE SUPREME COURT TRANSFORMED FAIR USE?

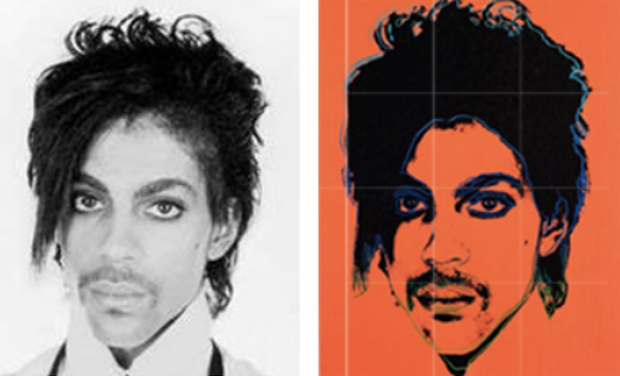

Since the Supreme Court decision involving the 2 Live Crew’s parody version of Roy Orbison’s song “Pretty Woman,” the touchstone of fair use analysis in copyright infringement cases has been whether the new work is “transformative” of the original. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). But this emphasis on “transforming” the original work created a tension with the right of the copyright holder to own works “derived” from the original. 17 U.S.C. § 106. When is “transformation” fair use and when is it an infringing “derivation?” In the recently decided case involving Andy Warhol’s adaptation of a photograph by Lynn Goldsmith of music icon Prince, a seven-justice majority tried to reconcile the conflict between fair use and the right of a copyright holder to own derivative works. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf. In an exercise of textualism, Justice Sotomayor, writing for the majority, returned to the language of § 107: “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes …” [The first of the four factors to be considered in fair use analysis]. The “purpose and character” of both the Goldsmith photograph and the Warhol print are the same, Justice Sotomayor concluded, namely publication and sale of a visual image of Prince in magazines [“…portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince”]. “Transforming” the work, as Warhol did by adjusting the image and colorizing it, was not “transformative” for purposes of fair use analysis – whereas the 2 Live Crew parody of “Pretty Woman” was transformative because its purpose was to comment upon and mock the original song (even though both were recorded musical works). Much note has been made of the sharp dissent by Justice Kagan, a justice more often aligned with Justice Sotomayor. Writing almost a lesson on art appreciation, Justice Kagan, joined only by Chief Justice Roberts, criticized her colleagues for failing to appreciate the creativity involved in the Warhol re-creation of the Goldsmith photo. What will this new direction from the Court mean for fair use analysis in music infringement cases? If the “purpose and character” of the allegedly offending song is the same as the original (e.g., phonorecords), it will be difficult to see how a new song that includes elements of an earlier one will succeed on the first factor. What about AI generated music? Again, if the “purpose and character” of the AI generated song is the same as the source material, it would seem a fair use defense will be hard to sustain. Time will tell, as new cases arise and lower courts attempt to tease out the implications of Warhol, but it may turn out that the “Pretty Woman” parody case will become something of a unicorn limited to its specific facts, rather than a sweeping directive to give a pass card to any work that purports to be transformative. A fair use defense may prove harder to sustain and the Supreme Court may have just added significantly to scope of the “bundle of rights” held by copyright owners.

ARE MELODIES PUBLIC DOMAIN?

Damien Riehl is a lawyer, musician, computer programmer and foe of copyright law. Melodies, he believes, should be free for all to use. To prove his point, Riehl recently wrote an algorithm to generate what he claims to be every possible melody that can be composed from the standard western 12 tone scale — 68 billion files in all. Then he made these available on Creative Commons on a zero-license basis, and poof! (Riehl claims) every possible melody is effectively now in the public domain! That should be the end of copyright infringement actions based on melody, argues Riehl, but commentators are skeptical. So far, the US Copyright Office takes the position that works generated solely by a machine aren’t protected by copyright. If not, then Riehl would not “own” the files his algorithm generated, and therefore could not make them available by license. Also, independent creation is a basis for copyright protection, and if songwriters are smart enough never to access Riehl’s files, they can still claim to be “authors” of songs they independently create. Still, Riehl’s arguments are provocative, and add to the ever more intense debate over the future of music in the AI era. For background, see https://music3point0.com/2023/05/12/heres-why-all-melodies-should-be-free-to-use/.

AI UPDATE: NO LONGER A THEORETICAL ISSUE

The AI Age is upon us, and problems that were the subject only of theoretical interest are now taking place in real time. Here is a partial compendium of issues confronting the Copyright Office, the courts, and the creative industries:

In January of this year, Google released MusicLM, an “experimental AI” tool that can generate music from text prompts and humming. Who will own the music generated by this, and similar, computer programs? For more details, see https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/google-trained-experimental-ai-to-generate-high-fidelity-songs-from-text-prompts-now-its-available-to-the-public/

In April of this year a “deep fake” version of Drake was released on streaming services, only to be taken down after protest from Universal Music, see https://www.billboard.com/pro/fake-drake-ai-song-earned-millions-streams-get-paid/ and https://techcrunch.com/2023/04/26/grimes-ai-generated-drake-music-legal-issues/.

DRAKE OR FAKE?

But, around the same time, pop artist Grimes (legal name Claire Boucher) offered a 50% royalty to anyone who uses AI to create a recording that fakes her voice. See https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-65385382

These isolated cases may foretell the inundation of streaming platforms using AI generated music. One commentator, writing in Wired Magazine, put it this way: “There’s potential for a flood of AI generated content to be unleashed onto streaming platforms, competing with real people and their compositions for the attention of your ears.” See https://www.wired.com/story/ai-generated-music-streaming-services-copyright/

What will be the long-term impact of AI generated songs on songwriters and performers? Computers don’t demand royalties or residuals or go on strike.

Legislation generally plays catch-up with technology (twenty years elapsed between the passage of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the Music Modernization Act), but AI has caught the attention of legislators already. In both the House and the Senate, legislators are calling for initiatives to regulate AI before it’s too late to impact its development. See https://www.npr.org/2023/05/15/1175776384/congress-wants-regulate-ai-artificial-intelligence-lot-of-catching-up-to-do.

In an interesting twist, Congressman Ted Lieu of California enlisted ChatGPT to help him write a resolution to regulate AI. Lieu explained the need for early legislative intervention in these words: “You have all sorts of harms in the future we don’t know about, and so I think Congress should step up and look at ways to regulate.” See https://lieu.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/rep-lieu-introduces-first-federal-legislation-ever-written-artificial

THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE TAKES A POSITION ON AI GENERATED ART

In March of this year, the Copyright Office published a “statement of policy to clarify its practices for examining and registering works that contain material generated by the use of artificial intelligence technology.” Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, found at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-03-16/pdf/2023-05321.pdf. The Guidance starts with this leading premise: “It is well established that copyright can protect only material that is the product of human creativity. Most fundamentally, the term ‘author,’ which is used in both the Constitution and the Copyright Act, excludes non-humans.” But how “well-established” is this position? The term “author” is not defined by the Copyright Act (instead, the Act says only that copyright vests in the “author” upon creation). To support its position that only humans can be authors, the Copyright Office cites three precedents: a case from the 19th century affirming the copyright protection of photographs (Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 56 (1884)), and two Ninth Circuit opinions, one dealing with an attempt to copyright a work allegedly written by a “spiritual being” (Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, 114 F.3d 955, 957–59 (9th Cir. 1997)), and the other a claim of copyright for a photograph taken by a monkey (Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418, 426 (9th Cir.2018)). But, once this major premise is put forth, the balance of the Office’s guidance follows logically. “If a work’s traditional elements of authorship were produced by a machine, the work lacks human authorship and the Office will not register it.” Thus, “[w]hen an AI technology determines the expressive elements of its output, the generated material is not the product of human authorship.” But, what if a human uses AI as a tool, rather than as the sole generator of content? The Office recognized that AI involvement will not necessarily preclude registration; it will depend on the facts of each case. “In other cases, … , a work containing AI generated material will also contain sufficient human authorship to support a copyright claim.” The Office concludes: “In each case, what matters is the extent to which the human had creative control over the work’s expression and ‘actually formed’ the traditional elements of authorship.” Following the release of this Copyright Office directive, the Recording Academy issued a policy in line with the directive that works solely created by AI would not be eligible for Grammy nomination. However, works that contain AI generated materials can still be eligible if they contain substantial portions of human created materials. See https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/ai-music-grammys-1.6896423#:~:text=%22AI%2C%20or%20music%20that%20contains,Press%20about%20their%20upcoming%20awards. So far, so good. But, the devil will always be in the details of each claim for copyright registration.

IN A GRAPHIC NOVEL CASE, THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE DENIES REGISTRATION FOR AI GENERATED VISUALS BUT ALLOWS IT FOR HUMAN GENERATED TEXTS

In a graphic novel case (or should we say, in a novel graphic case?) the Copyright Office produced a Solomonic decision in February of this year, denying registration for the AI generated content, but allowing it for the text written by a living, human author, Zarya of the Dawn (Registration # VAu001480196) [Read the Office opinion letter here: https://www.copyright.gov/docs/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf].

After first registering the entire graphic novel, the Copyright Office re-opened the case following it becoming aware of statements on social media that the comic book had been created using Midjourney artificial intelligence. The Office analyzed each component of the graphic novel, and determined the text was human authored, hence subject to copyright protection, whereas the images, which were mostly generated by the AI program Midjourney, were not, except as modified by human action. The Office revised the work’s registration as follows: “[The] new registration cover[s] the original authorship that contributed to this work, namely, the ‘text’ and the ‘selection, coordination, and arrangement of text created by the author and artwork generated by artificial intelligence.’ … The new registration will explicitly exclude ‘artwork generated by artificial intelligence.’” Comment: In the case of a graphic novel, where image and text are separate, the Office’s analysis makes sense. But what about songs, where lyrics, melody, and harmony are fused into a single unitary work? Can the Office “unscramble the egg” in the same process? Future cases will have to tackle these questions.

AI LOSES IN COURT

In February this year the Copyright Office refused registration of the visual image “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” which, according to Dr. Stephen Thaler, was “authored” by an AI program he calls the “Creativity Machine.”

Dr. Thaler filed suit in federal court seeking a determination that the Copyright Office erred in this decision. Both sides, Dr. Thaler and the Copyright Office, moved for summary judgment, and the district court judge hearing the matter ruled in the Office’s favor on August 18th this year. Siding with the Office, the court ruled “United States copyright law protects only works of human creation.” In so ruling, the court relied heavily on the 19th precedent of Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884), which involved an iconic photograph of the British writer Oscar Wilde.

In that case, the Supreme Court considered whether the photograph was copyrightable, or merely an unoriginal recreation of reality. In holding that it was protected, the court observed the photographic result “represent[ed]” the “original intellectual conceptions of the author [photographer].” The court interpreted this decision to mean “[h]uman involvement in, and ultimate creative control over, the work at issue was key to the conclusion that the new type of work fell within the bounds of copyright” and that “[c]opyright has

never stretched so far, however, as to protect works generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand, as plaintiff urges here. Human authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright.” The court’s decision, which summarizes American law on this subject, makes interesting reading and can be see HERE. Under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a ruling on cross-motions for summary judgment brings the case to a close, making an appeal by Dr. Thaler the next step. It is not inconceivable the Supreme Court may eventually take up this issue to resolve the vexing question of “AI Authorship.”

SCORECARD FOR PENDING AI GENERATIVE ART CASES

The past year has seen an onslaught of court cases challenging the use of copyrighted material to “train” AI generative programs. Here is a partial compendium of pending cases:

- A US class action against GitHub, Microsoft and OpenAI, concerning the use of code from GitHub to train Copilot (see here)

- A US class action against Stability AI, Midjourney and DeviantArt, concerning the use of artistic works in training data (see here)

- A US action by Getty Images against Stability AI, concerning the use of artistic works in training data (see here)

- A lawsuit brought by comic Sarah Silverman against Meta alleging her copyrighted materials were copied and ingested as part of training its LLaMA (a set of large language models created and maintained by Defendant Meta) “designed to emit convincingly naturalistic text outputs in response to user prompts.” See complaint here:

It is safe to say that more lawsuits are on the way, as the creative community struggles with the impact of AI generated art on the rights and livelihoods of human artists!

Click here to continue to Judith Finell’s article, “Coming Next: AI Generative Music Issues.”

Don Franzen’s legal practice covers the spectrum of the entertainment industry, including recording, television, film, live entertainment, copyright, trademarks, endorsements, corporate, tax and visa issues, and non-profit organizations. His clients include composers, producers, vocal and instrumental artists, as well as performing arts organizations. In addition to providing business and legal advice, he has acted an as a producer on recording, video, and theatrical projects. He also has established an expertise in commercial civil litigation, including appellate practice (State and Federal). He has lectured on entertainment law for Eastman School of Music, the Santa Monica College Academy of Entertainment, the Colburn School of Music, the California Institute of the Arts, and is a visiting professor at the Berklee School of Music (Valencia, Spain). Since 2009 he has taught courses on music and the law at the Herb Albert School of Music, University of California Los Angeles, and effective 2016 has been appointed as an adjunct professor as part of its Music Industry Program. Since 1997 he has been chosen as a Fellow of the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Southern California. He serves as the Legal Affairs Editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and has authored various essays and book reviews on legal topics. He is a founding director of the Los Angeles Opera, and a director of Heyday Books, and the Denyce Graves Foundation. In addition to his native English, he speaks Spanish, Italian and conversational German. He is married to Dale Franzen and proud father of three children. He may be reached by e-mail at donfranzen@yourinsidetrack.net.

© 2023 Your Inside Track™ LLC

Your Inside Track™ reports on developments in the field of music and copyright, but it does not provide legal advice or opinions. Every case discussed depends on its particular facts and circumstances. Readers should always consult legal counsel and forensic experts as to any issue or matter of concern to them and not rely on the contents of this newsletter.