Second Edition

Transcending the Inverse Ratio Rule: Musicological Hierarchies Continue to Apply

Judith Finell, Musicologist

Clear and convincing evidence of access will not avoid the necessity of also proving substantial similarity since access without similarity cannot create an inference of copying.

(2 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright § 14.3~4 at 634.)

A split between the 6th and 9th Circuits regarding the inverse ratio rule in music copyright disputes has emerged following a series of decisions made on the protectability of a collection of musical elements. The 9th Circuit has abolished the rule,[1] while the 6th Circuit has thus far maintained it.[2] The split should, however, have no impact on the musicological analysis performed in either circuit—nor should it subvert the specific elements of musical expression considered by the courts. While proof of access is an essential part of a copyright infringement claim, it is separate from the determination of musical similarity based on musicological examination.

For over five hundred years, pitch, rhythm (duration), harmony, and lyrics (if applicable) have formed the cornerstone of western musical expression. They define a musical work’s identity and distinctiveness. While configurations of these primary musical elements have evolved over time due to cultural influences, these basic traits have remained fundamental. While technology has also evolved, adding new dimension to composers’ toolboxes, melody has remained crucial to musical expression, and to its protection. Judge Sylvester J. Ryan referred to melody as the “finger prints” of the musical composition in Northern Music Corp. v. King Record Distributing Co.: “Musical composition is made up of rhythm, harmony, and melody … It is in the melody of the composition or the arrangement of notes or tones that originality must be found. It is the arrangement or succession of musical notes, which are the finger prints of the composition, and establish its identity.”[3]

The inverse ratio rule formulated a measurement whereby if high access was shown, then the musical proof required to establish substantial similarity could be lower. Inversely, if the access was low, then the proof of musical similarity, as a counterweight, had to be high. The need to prove a high degree of similarity gave rise to the collective similarities described in the cases discussed below, from Krofft v. McDonald’s (1977)[4] through Gray v. Perry (2020).[5] In some music, such as Marvin Gaye’s song “Got To Give It Up” compared to Pharrell Williams’ song “Blurred Lines,” the collective musical features form a similar design pattern to which I referred as a “constellation” in my testimony.[6]

Several years after the “Blurred Lines” trial, the 9th Circuit abolished the inverse ratio rule.[7] However, regardless of the future of the inverse ratio rule, the musical comparison process to determine substantial similarity is separate from the fact of access. As a practical matter, even if a songwriter were exposed knowingly to a previous song, this does not mean that the latter song will become similar enough in its own musical traits to the previous song to give rise to a successful accusation of infringement. Actual similarity can only be determined with an objective technical comparison conducted by a qualified musical analyst.

The opinions published in the cases below recognized collective similarities between works, and either dismissed or embraced them, depending on their degree of similarity and originality. For example, in their opinions on the musicological comparisons made of similar elements, some of the judges have referred to “trite”[8] melodic features as “building blocks,” found in prior art, undeserving of protection. Some of the features discussed by the judges and experts were non-compositional—such as [musical] arrangement and recording elements added after the composition was already intact, including the fade ending in Three Boys v. Bolton[9] and timbre in Gray v. Perry. However, even in dismissing cases, judges have consistently cited melody—meaning the sequence of pitches and rhythms—as an important consideration in determining substantial similarity. The protectability of melody was validated in the early twentieth century by Judge Learned Hand. In 1910, he opined in Hein v. Harris, that the “collocation of notes, which constitutes the composition, becomes [the composer’s] own, even though strongly suggestive of what has preceded, and it ceases to become an invention, and becomes an infringement, only when the similarity is substantially a copy, so that to the ear of the average person the two melodies sound to be the same.”[10] Judge Snyder cites Judge Hand’s opinion in Fred Fisher, Inc. v. Dillingham (1924)[11] in the district court Gray v. Perry opinion to support “the proposition that even a ‘relatively small’ portion of an ‘entire work’ may receive protection if it is ‘qualitatively important’ in context.” In doing so, Judge Snyder’s opinion affirms and quotes Judge Hand further: “The Court also notes Judge Hand’s observations made nearly a century ago that an eight-note ostinato was ‘the proper subject’ of an infringement action since it comprised a ‘substantial component’ of the plaintiff’s copyrighted song.” Judge Snyder’s opinion was recently affirmed by the Ninth Circuit.[12]

Differing limitations and criteria have been applied to melody in subsequent opinions, such as in Elsmere Music, Inc. v. NBC,[13] cited by Judge Canby in Swirsky v. Carey,[14] that “four notes were substantial enough to be protected by copyright.” In contrast, Judge McKeown wrote in her Skidmore opinion that “[Courts] have never extended copyright protection to just a few notes. Instead, we have held that ‘a four-note sequence common in the music field’ is not the copyrightable expression in a song.”[15] Regardless of the number of notes cited, the principle remains that melodies are significant to court determinations of similarity in both qualitative and quantitative evaluations. Conflicting metrics for the number of pitches to garner protection as a melody in published opinions have established that there is no bright line rule applicable to every music copyright dispute.

Regardless of whether the inverse ratio measurement is removed from the equation entirely, judges will still require standardized criteria in order to evaluate music disputes on a case-by-case basis. This change reduces the similarity assessment decision to the most cellular musical level, giving primacy to melodic pitch, rhythm, harmony, lyrics, and any other distinctive compositional features.

The main elements that distinguish individual musical works in the same genre from one another are those very specific features of melody and lyrics, even when built on a formulaic series of chords. For example, of the over 5,000 songs within the blues genre, all share the classic 12-bar blues chord progression and template.[16] Yet, “Folsom Prison Blues” (Johnny Cash) and “Johnny B. Goode” (Chuck Berry) distinctly differ from one another precisely due to their individual melodies and lyrics.

In evaluating music enmeshed in plagiarism disputes, the foremost questions a musicologist addresses are:

- Are these works alike?

- If so, how are they alike?

- Are their underlying compositional features alike?

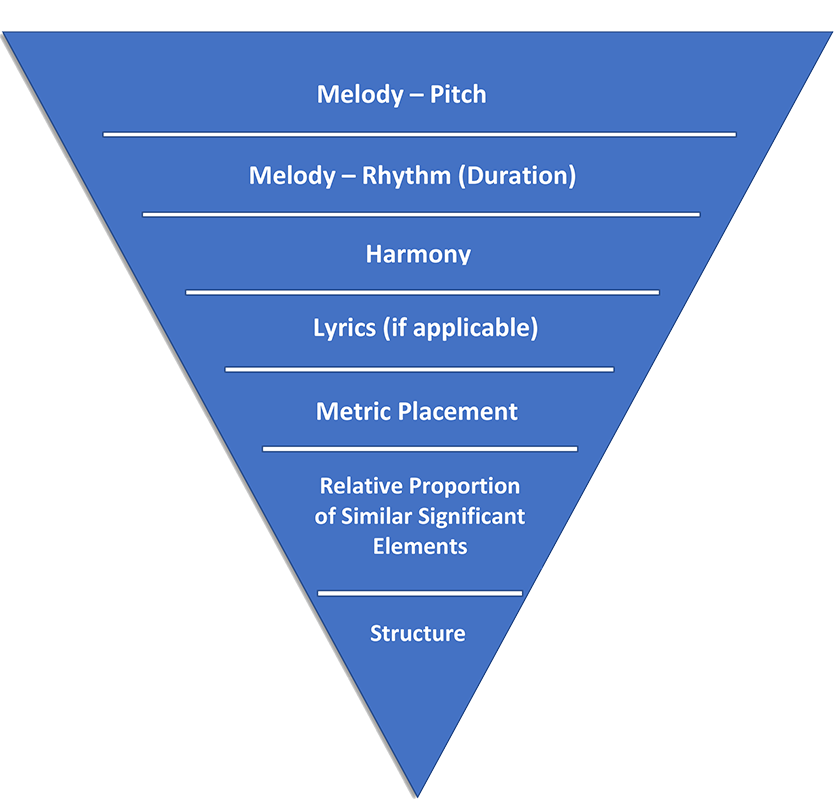

In my own musicological education and its application to copyright infringement disputes, I have developed and relied upon a hierarchy of musical features in assessing the degree of similarity between musical compositions. Most often, the elements at the top of the hierarchy carry greater weight than the lower ones.

Hierarchy of Elements in Assessing Substantial Similarity

- Melody – pitch

- Melody – rhythm (duration)

- Harmony

- Lyrics (if applicable)

- Metric placement

- Relative proportion of similar significant elements

- Structure

Graphically, as an inverted pyramid, with the most significant on top, and the least significant on the bottom, this hierarchy of elements could be represented like this:

Not all features are equally significant to a musical work, and some similarities are more fundamental to the expression of the works than others. There are also often overlaps between the hierarchical features. For example, metric placement describes the position of pitches and rhythms within the pattern of stressed and unstressed beats that propel a melody forward. Two songs can have a similar series of pitches and rhythms that do not align due to differing positions and stresses. The impact of stresses and position on musical expression is analogous to the English language, in which changing an emphasized syllable impacts the meaning of a word. For example, compare “inVALid” (adjective) to “INvalid” (noun), and “atTRIbute” (verb) to “ATtribute” (noun). The same sometimes applies to musical comparisons involving metric placement.

At times, the absence of one of these primary musical traits elevates the importance of items lower in the hierarchy. For example, many rap works contain rhythmic spoken lyrics with no melodic pitch. This means that the rhythm and rhyme scheme and underlying musical backdrop (referred to as the “bed”) become paramount in the comparison process over melodic elements. An extreme example of melodic minimalism are one-note songs, in which a single note is sung repeatedly with lyrics listing information. In opera, this genre is referred to as “catalogue arias,” and in musical theater, as “patter” songs. Examples include significant portions of “Johnny One Note” (Rodgers and Hammerstein), “One Note Samba” (Antônio Carlos Jobim), “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major General” (Gilbert and Sullivan), and “(Not) Getting Married Today” (Stephen Sondheim). In the case of one-note melodies, pitch becomes secondary to rhythm, harmony, and lyrics.

An example of musical minimalism being enforced was the 2002 dispute over the purported use of the composition 4’33” by leading avant-garde composer John Cage (1952). The work was silent, with a notated score containing directions to the silent performer(s). The John Cage Trust pursued songwriter Mike Batt for Batt’s work entitled “A One Minute Silence” for infringing the silent Cage work.[17] The case settled out of court for an undisclosed six-figure sum.[18] Ironically, these extreme examples still illustrate the importance of melody, as its total absence becomes an original feature in itself. My conclusions of whether substantial or striking similarity exists between two musical works result from a granular examination and analysis, considering this hierarchy of features.

The role of a musicologist in copyright disputes is to distill a musical work to its underlying compositional elements that form its expression—which is subject to the publishing copyright protection—as well as its recording, performance, and arrangement features, when applicable. Publishing copyright (©) and recording copyright (℗) elements are often conflated in dispute complaints and decisions. While judges in recent cases (including Gray v. Katy Perry and Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin) have dismissed similar generic or “trite” features as unworthy of protectability, I have seen no full dismissal of highly similar melodies as a matter of principle. Rather, melodic similarities continue to be considered most heavily prior to a decision on their originality and protectability.

Outcomes can differ when parties conflate publishing and recording copyrights. For example, the recording copyright is sometimes specifically at issue, too. When unlicensed digital sampling is at issue, analysis of sound waves and structure becomes important, but the evaluation of similarity still requires a distinction between the recordings and the underlying music compositions. Misperceptions as to the protectability of style are frequent despite early clarification by Judge Hand in Hein v. Harris, that “the right of the author of a musical composition is not affected by the fact that he has borrowed in general from the style of his predecessors.”[19]

The determination of a novel combination of individually unprotected elements as worthy of copyright protection far precedes the present-day cases. In his 1977 Krofft v. McDonald’s opinion, Judge Carter wrote that “it is the combination of many different elements which may command copyright protection because of its particular subjective quality.”[20] In her Three Boys v. Bolton (2001) opinion, Judge Nelson affirmed the district court’s decision precisely because the plaintiff’s expert showed “that there was copying of a combination of unprotectable elements.”[21] Three years later, in his Swirsky v. Carey opinion, Judge Canby wrote that “a substantial similarity can be found in a combination of elements, even if those elements are individually unprotected.”[22]

This statement has also been affirmed more recently. Though Skidmore v. Zeppelin and Gray v. Perry were ultimately decided in favor of the defendants, the principle of protectability of a novel combination of individually unprotectable elements was not challenged. In her 2020 en banc opinion on Skidmore v. Zeppelin, Judge McKeown wrote that “presenting a ‘combination of unprotectable elements’ without explaining how these elements are particularly selected and arranged amounts to nothing more than trying to copyright commonplace elements.”[23] Two weeks later, in her district court Gray v. Perry opinion, Judge Snyder clarified: “A collection of otherwise unprotected elements may be found eligible for copyright protection under the extrinsic test, but ‘only if those elements are numerous enough and their selection and arrangement original enough that their combination constitutes an original work of authorship.’”[24]

The combined elements within the comparison hierarchy is also affirmed by these decisions. In Three Boys v. Bolton, for example, the title “hook” phrases (including melody and lyrics) and the instrumental figures, but not the fade ending on the recording, were considered closely. In Swirsky v. Carey, pitch, rhythm, and harmony formed the foundation of the analysis, even when non-compositional recording/arrangement elements were included. Here, Judge Canby opined that “no approach can completely divorce pitch sequence and rhythm from harmonic chord progression, tempo, and key, and therefore support a conclusion that compositions are dissimilar as a matter of law.”[25] This collective similarities approach appeared in Williams v. Gaye,[26] where the constellation of melodic similarities in signature phrases, hooks, bass melodies, and word painting, were all based on notated melody, lyrics, and chord symbols affixed on the deposit copy lead sheet. In Skidmore v. Zeppelin,[27] melodic sequences were compared in pitch and rhythm, and the dual nature of an arpeggio as melody and harmony was explored. Most recently, in Gray v. Perry,[28] the ostinatos (short, repeating series of pitches) at issue were simple melodies built on repetition and distinctive timbre. The claimed use of similar timbre and texture—which are products of the arrangement and not the composition—was ultimately considered irrelevant to the underlying music.

Of the above cases, both Williams v. Gaye and Skidmore v. Zeppelin were rigorously limited in scope to the lead sheet’s musical elements, rather than stylistic, generic, or recording elements, due to the exclusion of original, pre-1978 recordings from the trial.[29]

These decisions have all revealed the primacy of melody in forming the underlying musical expression. There will continue to be experimentation with other sonic parameters by music creators, novel interrelated combinations of musical elements, and technologically-enabled access. It is unlikely, however, that anything will supplant melody in musical expression for a very long time. While the conflict between the 6th and 9th Circuits have challenged the threshold for musical similarity, neither Circuit has removed the essential traits of musical identity. With or without the inverse ratio rule, the same principles of musical analysis will apply to copyright infringement actions.

Dr. Geoffrey Pope assisted in writing and researching this article. Jessica Um also assisted in the research.

[1] Skidmore as Trustee for Randy Craig Wolfe Trust v. Led Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051 (9th Cir. 2020)

[2] Stromback v. New Line Cinema Eyeglasses 384 F.3d 283 (6th Cir. 2004); but see Enchant Christmas Light Maze & Market Ltd. v. Glowco, LLC 958 F.3d 532 (6th Cir. 2020)[in footnote 1, this 6th Circuit panel said: “… questions remain whether the inverse-ratio rule applies (or should apply) in our circuit. But we do not answer them today …”

[3] Northern Music Corp. v. King Record Distributing Co. 105 F.Supp. 393 (S.D. New York 1952).

[4] Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp., 562 F.2d 1157 (9th Cir.1977)

[5] Gray v. Perry, Case. No. No. 20-55401 (9th Cir. March 10, 2022).

[6] The author was testifying musicology expert for the Marvin Gaye estate in Williams v. Gaye.

[7] See footnote 1, supra.

[8] This descriptor has been applied to unprotected creative elements in numerous cases including the recent Gray v. Perry.

[9] Three Boys Music Corp. v. Bolton 212 F.3d 477 (9th Cir. 2000).

[10] Hein v. Harris 175 F. 875 (S.D.N.Y. 1910).

[11] Fred Fisher, Inc., v. Dillingham 298 F. 145 (S.D.N.Y. 1924).

[12] See Note 5, supra.

[13] Elsmere Music, Inc. v. National Broadcasting Co., Inc. 482 F.Supp. 741 (S.D.NY. 1980), affirmed 623 F.2d 252 (2nd Cir.1980).

[14] Swirsky v. Carey, 376 F.3d 841 (9th Cir. 2004).

[15] Judge McKeown quotes here from the Judge Carter opinion for Granite Music Corp. v. United Artists, 532 F.2d 718 (9th Cir. 1976)

[16] See, e.g., https://www.guitar-chord.org/articles/blues-progressions.html

[17] https://edition.cnn.com/2002/SHOWBIZ/Music/09/23/uk.silence/

[18] Id.

[19] See Note 10, supra.

[20] See Note 4, supra.

[21] See Note 9, supra.

[22] See Note 14, supra.

[23] See Note 1, supra.

[24] Gray v. Perry, Slip Opinion 2020 WL 1275221 (C.D. California March 16, 2020). Here Judge Snyder quotes from Judge Ronald M. Gould’s opinion in Satava v. Lowry, 323 F.3d 805 (9th Cir. 2003).

[25] See Note 14, supra.

[26] Williams v. Gaye, 895 F.3d 1106 (9th Cir. 2018)

[27] See Note 1, supra.

[28] See Note 5, supra.

[29] The decision of the trial court Judge Klausner in Skidmore v. Zeppelin to limit the elements to be considered to the lead sheet was affirmed by the 9th Circuit. Skidmore as Trustee for Randy Craig Wolfe Trust v. Led Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051 (9th Cir. 2020)

Judith Finell is a musicologist and the president of Judith Finell MusicServices Inc., a music consulting firm in New York and Los Angeles, founded 25 years ago in New York. Since then, she has served as consultant and expert witness involving music copyright infringement, advised on artist career and project development, and a wide variety of music industry topics. Recently, Ms. Finell was honored to be the 2018 commencement speaker at UCLA’s Herb Albert School of Music. She was also interviewed by NBC/Universal for a 2018 documentary entitled “The Universality of Music,” in which she discussed the ways in which she sees music as being an international language that can bridge cultural barriers that spoken language does not.

Judith Finell was the testifying expert for the Marvin Gaye family in the milestone “Blurred Lines” case in Federal Court. She has testified in many other notable copyright infringement trials over the past 20 years. She and her team of musicologists regularly advise HBO, Lionsgate, Grey Advertising, CBS, Warner, Disney, and Sony Pictures on musical works for their commercials, films, and television series. Ms. Finell also frequently advises attorneys, advertising agencies, entertainment and recording companies, publishing firms, and musicians, addressing copyright issues, including those arising from digital sampling, electronic technology and Internet musical usage.

Ms. Finell was invited to teach forensic musicology at UCLA in 2018, where she continues to teach the only such course in the country. She holds an M.A. degree in musicology from the University of California at Berkeley and a B.A. from UCLA in piano performance. She has written numerous articles and a book in the area of contemporary music and copyright infringement and has appeared in trials on Court TV and before the American Intellectual Property Law Association. She is a trustee of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A., and has appeared as a guest lecturer at the law schools of Harvard University, UCLA, Stanford, Columbia, Vanderbilt, George Washington, NYU, and Fordham, as well as the Beverly Hills Bar Assn., LA Copyright Society, and the Association of Independent Music Publishers. She may be reached by email at judithfinell@yourinsidetrack.net.

© 2023 Your Inside Track LLC

Your Inside Track reports on developments in the field of music and copyright, but it does not provide legal advise or opinions. Every case depends on its particular facts and circumstances. Readers should always consult legal counsel and forensic experts as to any issue or matter of concern to them and not rely on the contents of this newsletter.