Third Edition

Frenemies: Collaboration and Conflict between Music Creators and Digital Platforms

Ingenuity and technology continue to partner in making music more central to our lives. The pandemic has been a catalyst for new platforms for musical expressivity and circulation. With such social media as TikTok, the building of international audiences continues to expand beyond any earlier time. The regulation of the industry in protecting music copyright holders has evolved more gradually as has the music compensation system—lagging far behind music’s high-speed technological enablers.

In the past two decades, the affordability of powerful home computers capable of sophisticated digital audio and video work have given creators access to tools rarely before used outside of professional recording studios. This environment has democratized not only music-making, but also its distribution, accessibility, and earnings opportunities. A symbiotic relationship between the more rigidly structured music industry, and the ever-changing music creation and distribution environment has developed. Accommodating one another in order to foster success and growth has become a challenge.

Historically, music and technology have long partnered to enhance modes of creation and audience access. The printing press expanded the opportunities for music to be heard, distributed, performed, and developed by musicians. Through the twentieth century, inventions expanding music’s reach, including the phonograph, radio, television, photocopier, and compact disc, engendered love-hate responses from the music industry and its regulatory guardians. The twentieth century culminated in a wild west of digital sampling and filesharing, followed by legal disputes resulting in the takedown of filesharing applications and the forced emergence of a licensing mechanism for the rampant digital sampling that was taking place.

Since the pandemic began in 2020, there has been an explosion of musical creation and a dramatic growth of new audiences. Some of these new developments and the legal challenges they pose will be discussed below.

Gaming-Enabled Music: Creation and Usage

Videogame music, in particular, has changed tremendously, now basing music creation on game-player actions. The accompanimental underscore to many games now can change based on game-player actions. This is often achieved through the addition and subtraction of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic layers to the musical score, which are triggered by the game-player’s progress through the game. However, the exact configurations and durations of each layer, in real-time, are dependent on the player’s own choices and actions. The game-player can, in effect, mold pre-existing music as virtual musical “clay” to accompany game activities.

In addition to the underscore layers, the use of licensed third-party songs as part of the videogame package often conflicts with the needs of the game developers. For example, Rockstar Games has a long history of removing music from its Grand Theft Auto games when song licenses have expired. Some users have found this invasive because the company removed this music from the users’ own devices via an update patch to a game that they had already purchased. It is tantamount to a customer purchasing a car with a crucial part like an engine being removed by the manufacturer after its purchase. The songs used in the game are operating under a licensing protocol at odds with the videogame in which they are housed. This presents a challenge for attorneys formulating agreements between game developers and songwriters whose works are incorporated in the game.

Virtual Performances/Virtual Reality Concerts

Broadcasts of performances have now entered a new level beyond terrestrial radio, television, and simulcasts. Virtual reality and interactive performances in the metaverse from avatars representing the musicians operating them have become a big part of the industry. A prominent example is the artist Lil Nas X’s virtual performance within the game environment of Fortnite in 2020.

The nearly unlimited attendee capacity of online venues has also impacted the music industry. Traditionally, music and performance royalty yields have been based largely on the audience size within a brick-and-mortar concert hall. Virtual concert attendance has dramatically grown, due to the pandemic shutdown of live performance halls in 2020, stimulating the virtual audience numbers to grow from thousands to millions. Live concert venue capacities range from intimate 50-seat recital halls to stadiums seating 30,000, with finite seating that impacts the dollar amount that performing rights organizations (“PROs”) pay in royalties to their constituent composers. For example, Carnegie Hall in New York seats approximately 2,700, Madison Square Garden 19,500, the Hollywood Bowl 18,000, and Yankee Stadium 50,000. The royalty system was designed to pay composers public performance royalties based on the audience size, number of repeat performances, and ticket sales. These metrics have changed with the technological expansion of virtual audiences. For example, when a concert is streamed world-wide, with nearly an infinite audience capacity, the numbers multiply dramatically.

Quantifying and defining the number of internet users attending a virtual event has become more specific and granular than was previously possible for PROs monitoring public performance payments to composers. Present-day virtual attendance reports yield more than sheer audience numbers, and can include demographic and internet browsing information allowing creators, distributors, and marketers to target potential viewers and future customers.

Additional developments in the concert field, including advances in hologram technology, allow the creation and performance of musical works by realistic-appearing live or deceased artists. Matters of privacy and rights of publicity in virtual environments are also a concern.

Social Media

Developments have been rapid in this arena. TikTok, a platform that enables the use of third-party audio in user videos, has presented many challenges. Additional social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, redistribute TikTok content. While enlarging the reach of these initial TikTok videos, this practice also challenges the limitations normally enforced by copyright laws and music licensing agreements. New considerations and media may demand newly adapted agreements.

In terms of monitoring usage, YouTube Content ID now provides copyright owners whose work is identified in other users’ videos a streamlined alternative process for removing, blocking, or monetizing the use of that work. This option differs from a formal takedown notice as issued by a music publisher or record label or a copyright infringement claim in federal court. Rather, Content ID potentially allows creators and users to achieve mutually-beneficial solutions.

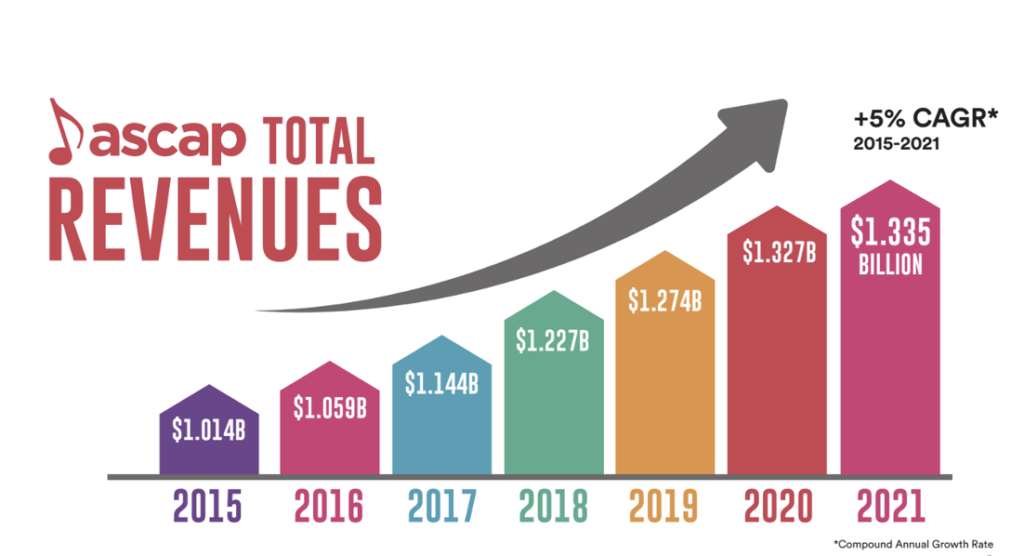

There has also been an explosion in the number of public performances of music licensed and tracked by the PROs on digital audio streaming services, such as Spotify, Apple Music, Pandora and the like. From 2015 to 2021, ASCAP reported performance royalty revenues as expanding from $1.01 billion to 1.3 billion, as shown below, in part due to the growth in digital audio performances:

More impactful than most other world events, the pandemic encouraged two years of new musical collaboration models driven by social isolation, venue shut-downs, and restricted travel. The advent of near real-time web audio and video conferencing has allowed for live musical collaborations formally limited to onsite studio environments. More traditional modes of digital collaboration have become popularized too, such as musicians overdubbing one another from different locations and times. The effectiveness of these techniques has been increased by the affordability of high quality home studio equipment, and advances in video and audio capture on smartphones. However, the unauthorized use of third-party materials, such as “beats,” imbedded in new musical works is rampant, and due to be addressed by the industry and its legal representatives.

Artificial Intelligence-Created Music

Finally, as artificial intelligence uses continue to grow, protection and compensation for AI-created music remains to be addressed, given the current determination by the United States Copyright Office that only human-created artistic expression is subject to copyright protection. Further, the use of artificial intelligence in interpolating existing recordings and performances via deep learning creates the potential for unauthorized uses, including “deepfake” music videos, in which artificial content is created that realistically resembles someone’s likeness, but whose words and actions are programmed by third-party users without permission. This raises first amendment, rights of publicity, fraud, fair use, parody, and many other issues.

The relationship between technological developers, user-programmers, and composers—and the music copyright and compensations systems—will continue to evolve. Most likely, new forms of litigation and enforcement will emerge in an effort to define the limitations and extensions of creativity protection. It should be a wild ride, filled with unexpected innovation and new challenges to the creative process.

Dr. Geoffrey Pope assisted in the writing of this article.

Judith Finell is a musicologist and the president of Judith Finell MusicServices Inc., a music consulting firm in New York and Los Angeles, founded 25 years ago in New York. Since then, she has served as consultant and expert witness involving music copyright infringement, advised on artist career and project development, and a wide variety of music industry topics. Recently, Ms. Finell was honored to be the 2018 commencement speaker at UCLA’s Herb Albert School of Music. She was also interviewed by NBC/Universal for a 2018 documentary entitled “The Universality of Music,” in which she discussed the ways in which she sees music as being an international language that can bridge cultural barriers that spoken language does not.

Judith Finell was the testifying expert for the Marvin Gaye family in the milestone “Blurred Lines” case in Federal Court. She has testified in many other notable copyright infringement trials over the past 20 years. She and her team of musicologists regularly advise HBO, Lionsgate, Grey Advertising, CBS, Warner, Disney, and Sony Pictures on musical works for their commercials, films, and television series. Ms. Finell also frequently advises attorneys, advertising agencies, entertainment and recording companies, publishing firms, and musicians, addressing copyright issues, including those arising from digital sampling, electronic technology and Internet musical usage.

Ms. Finell was invited to teach forensic musicology at UCLA in 2018, where she continues to teach the only such course in the country. She holds an M.A. degree in musicology from the University of California at Berkeley and a B.A. from UCLA in piano performance. She has written numerous articles and a book in the area of contemporary music and copyright infringement and has appeared in trials on Court TV and before the American Intellectual Property Law Association. She is a trustee of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A., and has appeared as a guest lecturer at the law schools of Harvard University, UCLA, Stanford, Columbia, Vanderbilt, George Washington, NYU, and Fordham, as well as the Beverly Hills Bar Assn., LA Copyright Society, and the Association of Independent Music Publishers. She may be reached by email at judithfinell@yourinsidetrack.net.

© 2022 Your Inside Track™ LLC

Your Inside Track™ reports on developments in the field of music and copyright, but it does not provide legal advice or opinions. Every case discussed depends on its particular facts and circumstances. Readers should always consult legal counsel and forensic experts as to any issue or matter of concern to them and not rely on the contents of this newsletter.